RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – It started off so innocently – people safely secure in their homes. Bolivia had just undergone a revolution that kept people from moving beyond their immediate neighborhoods for 21 days. How different could this be? Three months into the coronavirus quarantine, life is dystopian—horrifying, raw, wretched. Even the rich and comfortable are scared. Predictions become reality with stunning speed even as COVID-19 moves in like a slow-moving tank. But the scariest prediction is this: An infection in Bolivia will be a death sentence – by drowning in yourself, by yourself.

With a new government in place after toppling the 14-year reign of Evo Morales, the rookie team is questioned from all sides. Is the economic carnage worth it to stop the slaughter of its people? Is the government guilty for imposing its will too heavily? Too heartlessly? Are the people guilty for not caving-in and obeying mindlessly? COVID is a knife in the belly of the country, and it twists slowly. Fear is a constant hammer on the head. The virus takes its own time. It remains hidden in streets and in the jungles. Then it throbs and kills. The plot does not turn like the revolution. There is no end in sight.

“In a way, everything [the government in] Bolivia tries to do gets met with political opposition. If they quarantine the population, the opposition screams ‘We need to work!’ If they make the quarantine more flexible the opposition screams ‘The government wants us to die!’,” explains Kelly Barton, an American business-owner who resides in the central city of Cochabamba.

“It feels like now the real epidemic will start,” says Michael Kiehne, a German businessman in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, capital of a department bordering Brazil. It feels so because people are going out much more. “We are three months into quarantine and not much was prepared in all regions,” says Kiehne, “So people don’t listen anymore because there is no trust left.” Four telecommunication antennas were burned by people fearing it was the government using 5G technology to spread COVID-19, which prompted the government to clarify, “5G does not spread coronavirus,” and “There is no 5G technology in Bolivia today.”

In the streets the children of local merchants play on the dirt, putting in their mouths the first thing they find, relates Rucena Rodriguez Quiñones, an international ONG consultant who lives in the outskirts of Santa Cruz. “There is a lack of conscience. Others think it is all a hoax by the right and go out without protection. The markets are full of Venezuelans begging for food, neighborhood committees looking for food. They know the danger, but they have no other option,” says Rodriguez Quiñones. “Get COVID or see your children starve to death.”

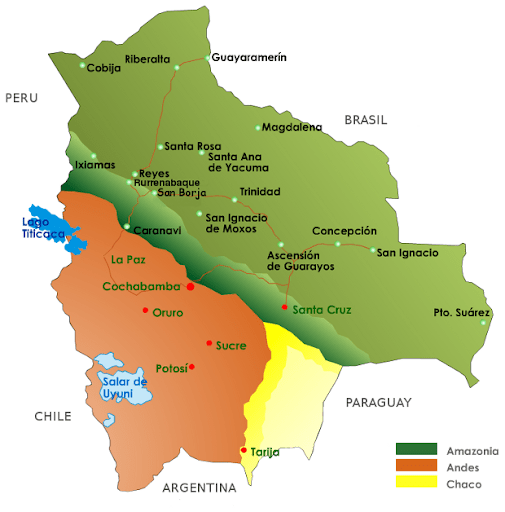

This is not the Bolivia of the mountains and the llamas, it is the Bolivia of COVID-19: it is the far eastern regions of Santa Cruz and Beni that comprise most of Bolivia’s 3400 km border with Brazil that are worst-hit. Sixty thousand Brazilians live in the area; some attend medical school there.

“There are zero winners,” says Barton. “People who aren’t scared to death, are dying. The streets are full of people putting imaginary needs over personal safety. Some needs are real, but sheer volume tells me people are inventing reasons to be out and about.” Fear is wisdom in the face of danger.

Hospitals are collapsing. They do not have space available, nor medical personnel, nor personal protection but I know people who still blindly think “Oh, mom fell, nothing is broken but let’s take her to the hospital to get her checked out,” not realizing that the sick and dying, plus their likely infected friends and family, are all in the streets surrounding that hospital, and in its halls and lobbies,” said Barton,

“It’s unbelievable,” says Kiehne, who resides in the tony Equipetrol neighborhood of Santa Cruz. He is incensed that an acquaintance has just informed him that she has COVID-19. “Then I see photos from two days ago, celebrating her birthday with a lot of people.” This will soon lead to photos like what we saw from Ecuador, believes Kiehne. “How can they risk other’s lives like that?” The surreal nature of the situation does not escape him. “Where I live it is just like a sci-fi movie.”

“I suppose there are people who have not even gone out their door,” says Rodriquez Quiñones, who lives in beyond-the-tracks Santa Cruz. When this hit, it made stark the class differences, she says, highlighting the difference with the privileged neighborhoods. “Where I live there is no delivery service; to go to the market for food is a dangerous feat. My sisters and I refer to the one who goes shopping as a ‘tribute’,” said Rodriguez Quiñones in a gallows humor reference to the dystopian movie “The Hunger Games.”

But then the mood turns suddenly somber. “The cases began to add up, and just like that it was no longer just numbers on tv, it was your neighbor, your cousin, your grandfather. The doctors started to die, nurses, people from the municipality,” she said with noticeable angst. “And then came the news of friends who died.” When the regional governor’s Health Secretary announced that the entire State Health Department (SEDES) staff was in quarantine for being infected, that is when the dam broke, explains Rodriguez Quiñones.

“The ones who were supposed to protect us were now all sick and in quarantine.” Then it got worse. “Two weeks ago, we began to see videos of hospitals rejecting the sick for lack of room, and we saw them die at the doors of hospitals. In my case,” she continues, “I have lost various colleagues and people I know from the teacher’s college – good teachers, they were young still; then died aunts and uncles of my friends, then brothers. It just exploded.”

“When I started to read the obituaries of my friends, all I could do is cry,” relates Rodriguez Quiñones., adding that every single one of them was buried without a funeral. “What hurt my soul was to remember them so full of life, community leaders, examplars– and overnight they died, drowned in themselves. I cannot imagine a more horrible death.” It is a grief that can’t be spoken. She wrote this down.

“Now that it is no longer a curiosity, now that my friends are dead and gone, now that my relatives have come down with it, I am afraid,” said Rodriguez Quiñones. “Not for my life, but as a mother my job is not done, but I am afraid of drowning in myself. It is that death that I fear the most.”

Yet, it is the plight of others that strikes her the most. “Each day, they come to my door asking for food for their community meals. At first, we could all help, but each day what we can do is less and less,” she says. “It is painful to go to the markets and to see people begging for food for their community meals, the musicians playing sad songs for a few coins, and the ladies in their selling stalls stressed for risking their lives every day.”

And every day the newspapers carry announcements of people begging for immune plasma from those who have survived the virus, or those seeking a bed in a hospital. “A doctor asked us in tears not to go out because there is no space, nor ventilators. He said that it would not matter if we had all the money in the world, there simply is no equipment.”

In far east Santa Cruz department, the border town of Puerto Suarez, across the El Pimiento river from the city of Corumbá in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, “they have no place to take care of patients, and people cannot receive medical attention on the Brazilian side because the border is closed. They have no resources. They are very concerned,” says Mayza Franco Peña, who grew up in the area and has never seen it this devastated.

But it is the large tract of Amazonian forest known as the Beni region that is in Bolivia’s most dire situation. When all the doctors and interns became infected, related Rodriguez Quiñones, doctors headed to Beni, risking their lives as they bought hundreds of doses of medicines, photocopied prescriptions and headed to the town squares to distribute the doses.

At the same time, notable Bolivian nephrologist and researcher Herland Vaca Díez called on Bolivian doctors to “combat and eradicate the virus in the country,” saying “Let’s diagnose and treat patients at home, let’s forget about the government.” He called for the use of the US-Federal Drug Administration (FDA) and World Health Organization (W.H.O.)-approved drug Ivermectin, used in Beni for veterinary parasite control, but widely and inexpensively available due to its inclusion on the W.H.O. model list of essential medicines.

Vaca Diez, along with another Bolivian doctor, moved on the anecdotal effectiveness of the drug as an antiviral and prescribed a flu-like treatment with Ivermectin, with much resistance from the country’s medical establishment.

“FDA is concerned about the health of consumers who may self-medicate by taking ivermectin products intended for animals, thinking they can be a substitute for ivermectin intended for humans. People should never take animal drugs, as the FDA has only evaluated their safety and effectiveness in the particular animal species for which they are labeled.

“These animal drugs can cause serious harm in people. People should not take any form of ivermectin unless it has been prescribed to them by a licensed health care provider and is obtained through a legitimate source,” says a June 2020 FDA letter titled “Do Not Use Ivermectin Intended for Animals as Treatment for COVID-19 in Humans,” adjunct to an abstract by the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia. The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Victoria, Australia concludes after clinical trials that the drug has SARS-CoV-2 viral-inhibiting properties: “Ivermectin therefore warrants further investigation for possible benefits in humans.”

Along the Beni-Santa Cruz road, in Santa Cruz’s Guarayos province, and serving an area that encompassed parts of Beni, the situation is critical. “The system has collapsed, patients are not receiving attention, all but one of the doctors are in quarantine because they have been infected,” relates Dr. Amada Daniella Gordillo Paz. “It is a desperate situation. It does not seem real. It seems like a horror film for all the things that are happening. People are dying. They are dying at home. Some get to the hospital already dead; others die of a heart attack for lack of air.” The province government has organized brigades to go into homes and into all corners to search for the sick and dead.

“Avei” is adios, goodbye in the indigenous Ava-Guarani language of the Beni lowlands. There, volunteer groups are trailing behind Guarayos. Their brigades are called Avei, they search for bodies in homes and the fields for a human and humane goodbye. People are overwhelmed. The government is overwhelmed. There are people across 12 million hectares of Beni wetlands.

In the Andean highlands things are calm, but the Bolivian tourist town of Uyuni is barren, reports Chris Sarage, the American owner of Minuteman Pizza. Pre-COVID, Uyuni was a magnet to tourists of all walks, the superrich, and uberadventurers trekking to the world-famous Uyuni Salt Flats. “People are fearful,” says Sarage. Most of the tour agencies are empty to save on rent. The town has lived off visitors for years. He will keep his restaurant closed at least until next year. “Most of my staff went back to their farms to herd llamas and quinoa.”

Back in the lowlands, fear rules: Rodriguez Quiñones comes back from the market and gargles furiously with hot water and bicarbonate, inhales “eucalyptus vapor, chamomile, and another of grandma’s concoctions.”

Symptoms are as frightening psychologically as physically, says Barton. “The times I have felt a sore throat or tiny fever, I have planned out my dying, death and after events. No sneeze is forgiven these days. But we take vitamin D, vitamin C, echinacea, and propolis. We wear masks and intermittently gargle with alkaline water and salt water. We disinfect religiously to ease our fears.”

Because here you die in hospitals, said Kiehne.