RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – “This is a caudal vertebra from the tail of this new dinosaur, it weighs between 20 and 25 kg.” Dissector in hand, like the one used by dentists, geologist Alberto Garrido begins his meticulous work in the laboratory of the Provincial Museum of Natural Sciences in Zapala, 1,300 kilometers southwest of Buenos Aires in the Argentine province of Neuquén.

The first elements analyzed of this 98 million-year-old giant titanosaur, from the sauropod branch, suggest that it may be the largest ever found in the world, according to a study published on January 20, 2021 by the scientific journal Cretaceous Research from the Netherlands.

What has been discovered so far are elements of the pelvic girdle, the pectoral girdle, and the first 24 vertebrae of the tail, that is, the lightest. “The weight of each dorsal vertebra would be about 300 kg,” says Alberto Garrido, 49, director of the Olsacher Museum since 2008, who has participated in many excavations in this region of southern Argentina, highly prolific in fossil remains.

“This newly discovered dinosaur has no name yet, its discovery is part of a scientific research project developed by our museum for a long time. What distinguishes it from the others, apart from its large size, is that it dates from the Lower Cretaceous, a period to which only 5% of the specimens found in the region correspond,” he explains, remaining evasive about the precise location of the excavation site. “We’ve had bad experiences in the past,” he justifies.

In 2013, a short distance from the unearthing of another dinosaur, three vertebrae popped out of the sediment. “Just by looking at them, we knew it was indeed a sauropod and a big one. By clearing out one side and the other we could see that the vertebrae were articulated; it had great potential,” recalls the geologist.

But before moving forward, the other excavation had to be concluded. To preserve them, the first bones were covered until 2015, when a team of five paleontologists and Alberto Garrido as the only geologist returned to the field.

With pickaxe and pneumatic hammer, a well-formed tail began to appear as an outcrop from the rock, and then the hip was revealed. “This dinosaur is supposed to be almost complete because everything we’ve been working on is in perfect joint condition,” says the geologist. “But the work is hard, we have to do it the old-fashioned way: pickaxe, iron cutter, crowbar … Our camp is a 50-minute walk from the deposit, forcing us to carry generators and other heavy equipment on our backs.”

A third of the animal was dug up and the lighter vertebrae were taken from the laboratory to the Olsacher Museum for the meticulous work of cleaning and preparation. And then the pandemic upset all plans…

Larger than the Patagotitan mayorum

Unable to work on-site due to strict social isolation measures imposed by the Argentine government in March 2020 to curb the spread of Covid-19, the scientists set about writing a report.

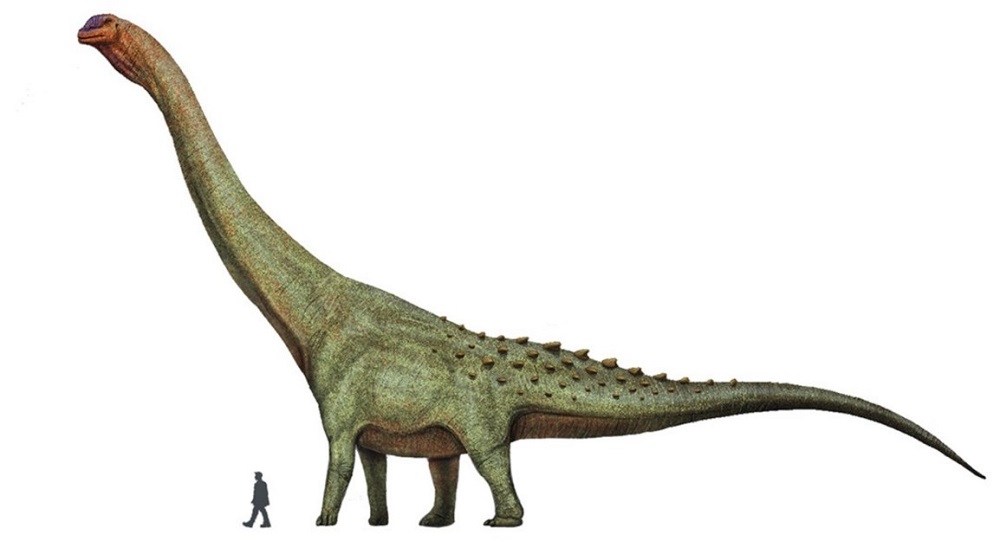

The first finding is that this dinosaur may have weighed between 70 and 80 tons and could be 10% larger than another discovered in 2017, the Patagotitan mayorum, which measured between 35 and 38 meters.

“These are estimated calculations. Clearly, it is larger than the Patagotitan. If it is almost complete, as everything suggests, we will be able to take more realistic measurements and also adjust those of other dinosaurs in the vicinity. There is still much to learn,” says Alberto Garrido.

Alberto was only ten years old in Plaza Huincul, province of Neuquén, 1,260 kilometers southwest of Buenos Aires, when he went to search the fields to collect arrowheads from the native inhabitants of the area: Mapuches, Araucanos, Gününa-kena.

“I started with the archaeological side, but very quickly I drifted to paleontology and geology,” he recalls. “Next to the arrowheads there were remains of dinosaurs and these bones fascinated me, I wanted to know why this animal had died there. For me, the bone is just one more piece in the context.” Since then, he has made his way in this field and has been called to participate in excavations in Canada, the United States, China, and Hungary, to name a few.

Sauropods moved in herds

The subsoil of Neuquén is full of oil and gas. This sedimentary basin, formed in the Upper Triassic period about 220 million years ago, is the main fossil energy reserve of the South American cone. Before the formation of the Andes, the region was regularly bathed by the waters of the Pacific, hence the presence of marine deposits in the middle of the continent.

Over the eras, current Patagonia has been home to deserts, deep seas, jungles, and then again huge deserts. In the Triassic period, a tear in the continental crust was the starting point for the development of the Neuquén Basin. This was the beginning of the tectonic breakup of Gondwana, when South America separated from Africa, producing phenomenal tears in the continental crust.

It was not until the beginning of the Jurassic period that an enormous depression gave birth to the present Neuquén Basin; then, at the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs, the region experienced a new marine invasion, this time from the East: the Atlantic Ocean.

In this chaotic and changing environment, the region was inhabited 220 million years ago by different species of dinosaurs, including titanosaurs like the one recently discovered, a herbivore quadruped with a long neck.

“With some exceptions, this is a dinosaur that had neither spikes nor armor to protect itself from carnivorous predators; their only defense was their imposing size,” recalls Alberto Garrido. “The mortality rate was probably very high, in their youth they were very easy prey. Their survival strategy was to grow quickly and in large quantities.”

“We understand this just by looking at huge deposits like the one discovered in the Auca Mahuida volcano area in 2017, which contains thousands of dinosaur eggs containing embryos, 70 million years old, spread over several levels and miles.

“All the information we’ve been able to gather points to the fact that these sauropods moved in herds, were in constant motion, spending much of the time feeding to maintain their colossal body mass, and no doubt had specific egg-laying locations.”

The craze for paleontology

Argentina is not an exception in terms of the number of fossil deposits. There are many in the United States and Canada, in China, as well as in Brazil, and smaller ones in Europe. For Alberto Garrido, “the difference is that here generally we find new species; our geology is very rich both by the immense extent of Patagonia and by other sedimentary basins resulting from the formation of the Andes: San Juan and La Rioja in the central-west, Salta in the north, and these ancient deposits are now on the surface of the earth where fossils outcrop.”

Argentina was one of the pioneer countries in paleontology in Latin America, under the influence of German scientists who formed the basis of local geology in the late 1870s. But, as far as dinosaurs are concerned, “we are a hundred years behind Europe and North America,” acknowledges Alberto Garrido. “It was not until the 1960s that a paleontologist from our country, José Bonaparte, began studying them and trained the first specialists.”

In fact, one species – Zapalasaurus Bonapartei – is named after him.

Local paleontology has grown rapidly in recent decades. For a long time a rare discipline, it has aroused interest and vocations thanks to the Jurassic Park saga. “After the first movie came out, young people started enrolling in universities to follow the career of paleontology. And today we have a mass not only of students but also of professionals who will certainly contribute to the development of the discipline,” says an optimistic Alberto Garrido.

And he concludes: “You have to walk a lot to find dinosaurs, the areas are so vast, there is so much to excavate. Along the way, we are often surprised by what we find, and this produces strong discussions. This is indeed one of the principles of science.”

Source: La Croix