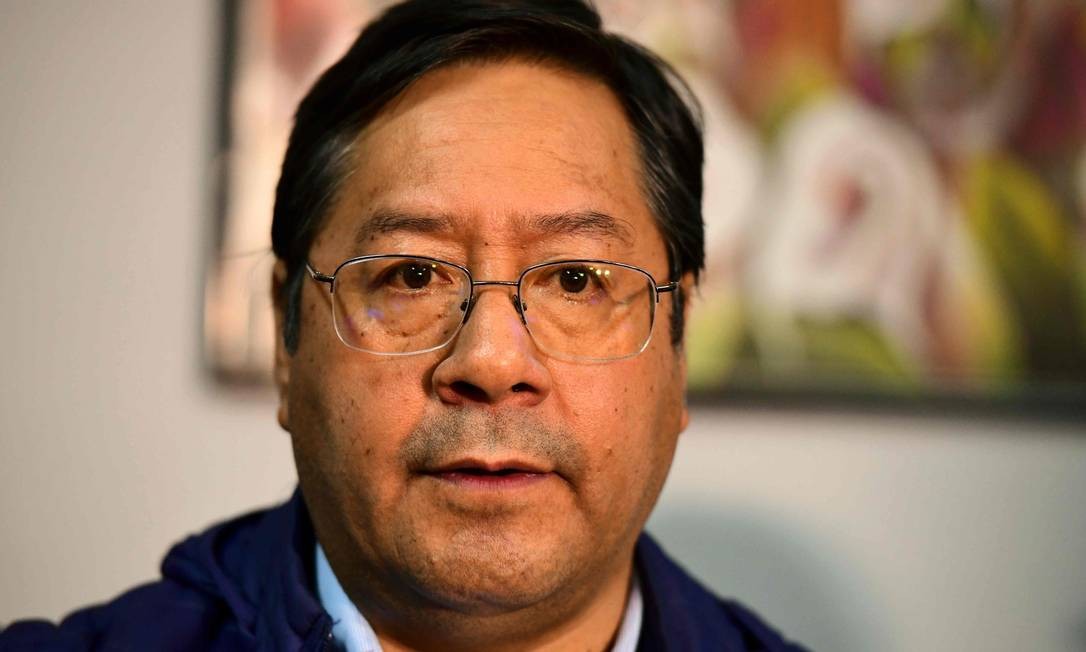

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Bolivia‘s hopes are pinned on Luis Arce, the Andean country’s president-elect. The ex-minister of Economy not only secured the votes of MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) supporters, but also those who want to see a reprise of the “economic miracle” that he worked under Evo Morales: almost a decade (2006-2014) of high growth and poverty reduction.

But the current scenario is very different. Arce will take power amid an unprecedented economic and health crisis that, according to experts, will not allow an easy replay of his achievements.

The Bolivian economy will drop 7.9 percent this year due to the pandemic crisis, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates. However, its rebound is expected to be fast, with a rebound of 5.6 percent in 2021.

“The economic crisis was a key and decisive factor in the election,” says Diego Von Vacano, professor of political science at Texas A&M University and advisor to Arce’s presidential campaign. His victory with 53 percent of the vote, according to preliminary results, suggests that many Bolivians who did not necessarily identify with the MAS gave him their vote, says Von Vacano.

“People began to realize that in coronavirus times when the economic crisis became more acute, it would be better to have an economist with a clearer mind to be able to tackle it,” he says.

Among the 11 million inhabitants, 34.6 percent of Bolivians live in poverty and 12.9 percent in extreme poverty. As in the rest of Latin American countries, the pandemic is expected to push many people from the middle to the lower classes. Arce’s economic plan states that, through support to the agricultural sector, his government will ensure food security.

From La Paz, economist Napoleón Pacheco says that if Arce “projected this image of a competent minister, of sound management, this is explained by an extraordinarily favorable external context. Evo Morales came to power at a crucial moment, when Brazil’s gas market was already open, after 20 years of Bolivian negotiations to sell in this market. There was a constellation of favorable factors without which Bolivia would not have been able to capitalize on the raw material price boom”.

This provided Arce with extraordinary resources to cover the country’s chronic excessive spending, says the expert, so there were budget surpluses for several consecutive years until commodity prices dropped again.

“The deficits came back at that time and Luis Arce never intended to reverse them, because it meant putting a brake on public investment. His motto was to tackle the slowdown of China and the economy through investment and deficit,” says Pacheco.

The State as an Economic Player

The Bolivian economic model developed by Arce considers the existence of two sectors: a “strategic surplus generator”, composed by the oil, mining and electric industries, and an “income and employment generator” sector, made up by the manufacturing industries, agriculture, cattle raising, building, tourism, among others. The first sector is in the State’s hands, making it the main player in the economy.

The goal is to transfer the surpluses to the second sector to “industrialize natural resources,” which has translated into major infrastructure works and the creation of dozens of other public companies. A wide range of social policies is also being financed.

How will this model be financed now that the export sector can no longer provide it with the resources it needs? According to Omar Yujra, a member of Arce’s economic advisory group, this will be first achieved by ceasing to pay the external debt for two years, which will mean savings of US$1.6 billion (R$9 billion) in capital and interest. In addition, a new tax will be introduced on large fortunes that will yield US$400 million per year, although it will only impact 10,000 people.

With this initial boost, the Arce Government will seek to support the three sectors that create the most jobs: manufacturing, agriculture, and domestic tourism. This way, it hopes to solve the most pressing issue at the moment: the lack of job openings, particularly for young people. “We will have a neo-protectionist approach: promoting domestic production with the greatest possible substitution of imports,” Yujra said. Following this logic, an attempt will be made to replace diesel imports – which produce a significant loss of foreign exchange – with domestic production of vegetable biodiesel.

Pacheco believes that Bolivia cannot rely on projects that have not yet been tested and that, in order to keep the country in operation, Arce will have no choice but to incur significant debts with international financial bodies, as Jeanine Áñez’s interim government has already begun to do. This solution, however, would be in contradiction with the new president’s intention to declare a temporary moratorium on foreign debt.

Bolivia boasts the world’s largest lithium resources that have not yet been commercialized. Lithium is a mineral essential to the production of batteries for cell phones, computers, and electric cars that promise to reduce carbon emissions and pollution on the planet; some even consider it “the new petroleum”. The economic potential of this substance to Bolivia is enormous, says Von Vacano.

But the country has not yet defined a course to market its reserves. For ideological reasons, MAS never wanted the country to limit itself to exporting lithium carbonate, which is the primary resource. Morales even dreamed of producing electric batteries “made in Bolivia”.

Arce will seek public-private partnerships, says Von Vacano, while maintaining the country’s sovereignty. This would mean a significant source of tax income if investors and private companies are found willing to work the reserves without privatizing them. The former Bolivian government was on this path with a joint-venture with the German company ACI Systems, which the resignation of Morales in November 2019 abruptly severed.

“Arce’s work will be very difficult, this is a very serious crisis,” Von Vacano says, “but I think that little by little he will succeed.”

Source: El País