RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Conexão Saúde is considered a successful model of how the pandemic could have been controlled.

Through mass testing, teleconsultation, food for those who need to remain in isolation, hygiene kits, and communications to fight fake news, a social project managed to reduce deaths from Covid-19 by 61% in Maré, a complex of 16 favelas in Rio de Janeiro, with some 140,000 residents.

In July 2020, the Covid-19 mortality rate in the region was 148 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. This May, it closed at 57 per 100,000. In the same period, the city of Rio jumped from 115 deaths per 100,000 to 233 per 100,000, an increase of 43%.

Created a year ago by Fiocruz (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) researchers and NGOs, with funding from Itaú-Unibanco’s Instituto Todos pela Saúde (All for Health Institute), Conexão Saúde is considered a successful model of how the pandemic could have been controlled, including in the most vulnerable areas, with science-based policies and coordinated initiatives among the federal, state, and municipal governments.

“The SUS [national health service] is widespread, but good strategies for pandemic control were not created, involving primary health care, for example. We lost a lot of time with this bizarre early treatment discussion, even among the science community,” says infectologist Fernando Bozza, Fiocruz researcher and one of the project’s coordinators.

Conexão Saúde began with an amalgamation of several initiatives. At the very start of the pandemic, Redes da Maré, an NGO operating in the region for 13 years, began distributing food baskets to the most vulnerable families.

“We saw that, along with food insecurity, people were reporting Covid symptoms, but they didn’t have access to testing or medical care, because they were afraid or because the system was very disorganized,” says Luna Arouca from Redes da Maré NGO and one of Conexão Saúde’s coordinators.

The NGO approached Fiocruz, which was studying the pandemic in the most vulnerable areas. Concurrently, another NGO, Dados do Bem (which develops testing applications and works with immunity analysis), SAS Brasil (a telehealth company), and other partners also joined the project.

“There used to be a concept that favela residents could not be isolated because of their housing conditions, the number of residents per room. We have shown that this is not true. It is possible to be safely isolated, provided there are adequate conditions for that,” says Bozza.

According to the researcher, one of the project’s greatest achievements was to look at the community and work with it in developing qualified communication strategies to control the pandemic.

“Health campaigns communicate very poorly with the population. With so much fake news being spread, it is essential to have qualified information like groups that already liaise in the community’s different social networks, on Instagram, in podcasts, and on TikTok. We have a tiktoker in the favela, Raphael [Vicente], with 1.8 million followers.”

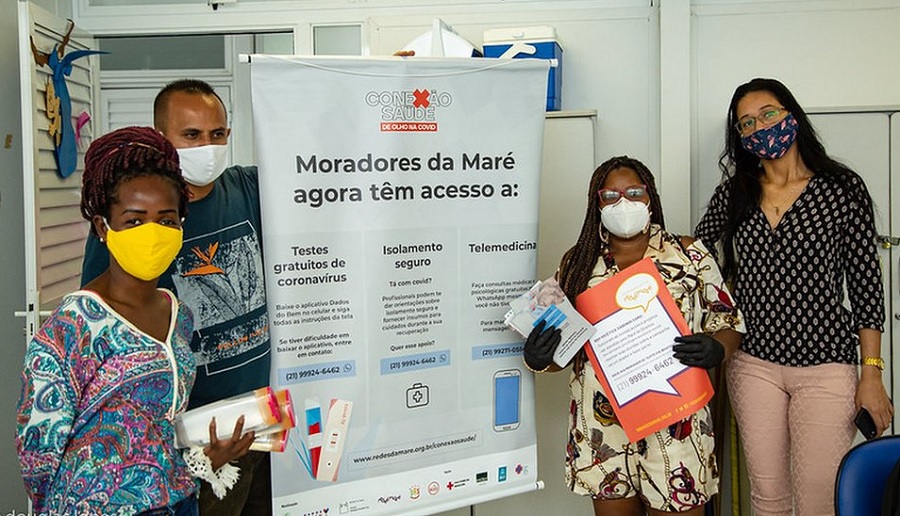

In addition to the various communication initiatives led by residents themselves, the project is based on three other fronts: free testing for Covid-19, online medical and psychological care, and food and hygiene assistance to ensure the isolation of those infected.

Conexão Saúde has performed over 25,000 serological and PCR tests, with a 16% positivity rate. By June 14, it had provided 4,201 medical and 1,792 psychological consultations. Tests are performed in a testing center set up in Maré, connected online to the Fiocruz laboratory. Results are available within 24 hours.

If a test is positive for Covid, a series of other actions are taken to monitor the infected person’s health and contain the spread of the disease. The other residents of the house are also tested.

Candy maker Tatiana Silva de Lima, 40, was one of the program’s beneficiaries. Last March, her son Victor Hugo, 14, was diagnosed positive for Covid-19 a month after on-site classes began. “First he had a headache, then diarrhea, and finally he couldn’t taste food anymore,” she recounts.

The mother approached the project and they were both tested for Covid-19. Her son’s test was positive, but hers was not: “Nevertheless, I was desperate because I take care of my bedridden grandmother, who is very ill.”

Two hours after her son’s positive result, Tatiana says she was contacted by a social worker and welcomed into the program. She was provided with a hygiene kit with chlorine, sanitizer gel, gloves and masks, and three meals a day (lunch, snack and dinner) for herself and her son for the duration of the boy’s isolation. Neither she nor the grandmother were infected.

“What was most impressive wasn’t even the food, which was great, well-seasoned. It was that every day someone would be in touch to check up on his symptoms. This gave us a great sense of security,” she says.

According to Luna Arouca, from Redes da Maré NGO and one of the coordinators of Conexão Saúde, this more humane part of the project is what the residents highlight the most when assessing the program.

“With the fact that we call every day to find out how people are doing, take the supplies they need, offer medical and psychological care, they feel cared for, they know they have a reference, someone worrying about them.”

She says that although Covid-19 infections are still occurring, since it is virtually impossible to prevent them in such a large community with so much circulation, the fact that deaths have been reduced is a great success.

For Eliana Sousa Silva, director of the NGO Redes da Maré, despite all of the project’s positive results, the whole process calls for public policies on health, education, employment, basic sanitation, and public safety, among others aimed at the community.

“Without this, there is great vulnerability. We can’t even advance to other fields because people don’t have the basics, like access to food.”

Luna Arouca reiterates. “These are historical structural issues that we are unable to address without permanent public policies. Often the government stops doing its job because it says the place is violent, it has no conditions. But we show that it is possible to do something well done, qualified, and deliver a quality service.”

The project should gain new fronts with the arrival of more partners. One of them will be the follow-up of women impacted by the pandemic due to the loss of relatives and/or income.