By Thábara Garcia in partnership with RioOnWatch

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Several leaders and organizers from the city’s favelas and urban peripheries, who for months have been helping with grassroots aid operations in their communities, say that the breakdown of how favela residents have received or lacked services during the pandemic should prompt larger reflections about Brazil’s social and economic paradigms.

In their view, the pandemic’s upheaval evidences the importance of robust social spending, territory-based investment, and an emphasis on mental health.

As of June, almost 50% of Brazilians lived in households that had received some kind of income support from an emergency aid stipend of R$600 (US$110) per month for unemployed and low-income adults. The aid has been of utmost importance to millions of Brazilians, many of them living in favelas.

On the other hand, the scarcity of high-quality health resources available to favela residents has proved deadly. In addition to favela residents facing more precarious access to public hospitals and clinics, public Social Assistance Reference Centers in cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Nova Iguaçu, and São Gonçalo work far over their intended capacities.

Many people “were already living in a reality where many losses are normalized, so Covid-19 is only one more threat to be dealt with,” said Fabbi Silva, who directs the social project Sponsor a Smile in Duque de Caxias, in the Baixada Fluminense lowland suburbs just north of Rio’s capital.

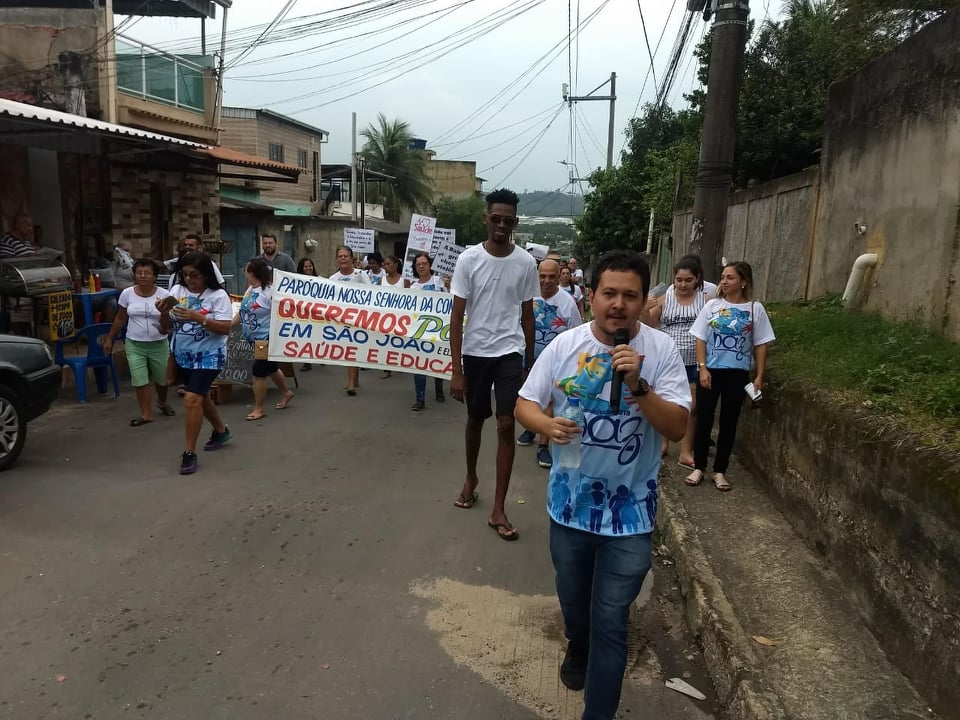

Douglas Almeida, an economist and longtime organizer from São João de Meriti. another town in the Baixada Fluminense, pointed to shifts underway, even in mainstream economic thinking, about what kind of economic policies are prudent.

Brazil’s pandemic emergency aid stipend will likely be extended in some form for several months, and even after the pandemic, Brazil’s government has signaled that it will expand the value and scope of cash transfers to low-income families. This is a step in the direction of a basic income for part of the population – and eventually a universal basic income, which a vocal community has demanded for years, but until recently, lay far outside of the mainstream of Brazilian economic policy.

Favela-based organizations have backed a public letter calling for a robust basic income to be implemented after the pandemic, funded by taxes on the wealthiest Brazilians and characterized by lack of barriers to access and lack of substitution of any existing social programs. Rio favela groups such as Rocinha Resists and Observatório de Favelas are signatories, as well as national groups such as Frente Favela Brasil.

Almeida said that the fact that government intervention in the economy became the main economic option during the pandemic shows that the market alone cannot cater to the needs of the poorest. Going forward, he said, “the necessary change for the economy is about valuing people and the collective over individualist models and accumulation.”

Even before the pandemic, influential world figures had been speaking out about the importance of such a re-examination. Almeida was one of the young Brazilians chosen to meet Pope Francis and to participate in a conference called “The Economy of Francesco” which aimed to debate pathways to a less unequal world.

Ingrid Siss, a psychologist from Rio’s City of God favela, said that the pandemic has also shown how care for vulnerable communities must include psychosocial care.

For favela residents, access to a reflective, psychosocial perspective during this crisis can be extremely powerful, she said. She believes that people will have learned a lot from this moment, “regardless of whether it is a new technique, a new tool, a way to produce efficient items of quality in new scenarios, or even a new level of awareness, because we have never been forced to be with ourselves as we have been.”

“We don’t have the possibility of escaping from what bothers us, as we used to do before,” she continued. “That’s why all of us feel invited to look at our inner selves. All these individual confrontations will take us collectively to a place we don’t even know yet.”

Community leaders stress that in order to turn the learning from the pandemic into action, it is crucial to have an individualized eye toward what has worked and what needs remain unmet in each territory.

Some very clear examples of unmet neets, said Almeida, include internet access, access to the system for emergency income payments, and public security policies that do not kill civilians, particularly black favela youth.

Community-based groups plan to continue to organize with wider networks in order to make these demands clear. The manifesto for a robust basic income is just one example of this; the efforts at Brazil’s Supreme Court to control police abuse of force in favelas is another. After hearing detailed arguments from favela organizers and human rights groups, in mid-August the court ruled in the favela activists’ favor and prohibited police shooting from helicopters, operations near schools and hospitals, and alterations to the scenes of a police shooting.

This article is part of RioOnWatch’s 2020 reporting partnership with The Rio Times now focused on the impacts of coronavirus on Rio’s favelas.