By Emily Zislis, in partnership with RioOnWatch

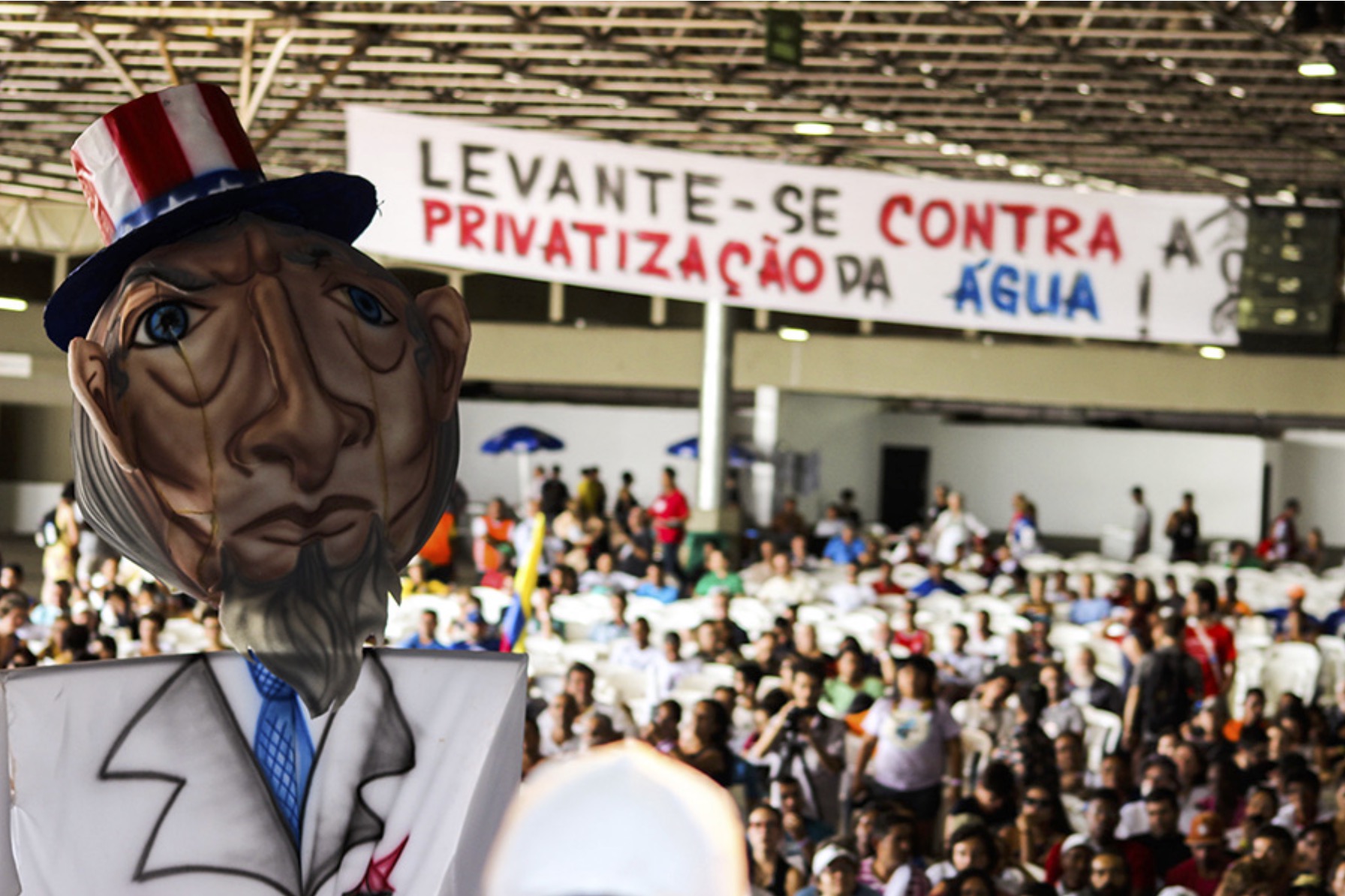

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The beginning of this contracting process has prompted fierce debate about whether a more privatized model of service provision can close longstanding inequalities of access to water and sewerage in places like favelas—and whether such privatization is appropriate, given CEDAE’s profitability.

The current plan to grant private concessions for CEDAE’s operations involves splitting Rio’s municipalities into four blocks that combine wealthier regions with those that severely lack basic sanitation infrastructure. While this model may encourage private investment in “unlucrative” communities, some believe it will subject citizens in the peripheries to exorbitant costs. Currently, 6% of Rio’s water is operated by the private sector; residents living in these regions pay up to 70% more for their water than do those serviced by CEDAE.

“The populations who don’t have access to sanitation or water supply are the poorest people of our state, living in the peripheries,” said doctoral student and geography professor Danilo Cerqueira at the first virtual public hearing about CEDAE’s privatization. Many in the audience voiced concerns that with privatization, water bills will go up for marginalized groups.

International research on the effectiveness of public versus private water companies conducted by Corporate Accountability International found that public and private water companies had comparable efficiencies. Globally, water privatization is sharply decreasing; over 90% of water services are publicly provided across the world today. Many cities around the world, including Paris, have undergone remunicipalization—returning water assets back to government ownership.

Going against this trend, in early 2021, Rio plans to auction off a contract for part of CEDAE’s operations in at least 46 of the state’s 92 municipalities. The commitment to hold this auction is part of a fiscal recovery regime underway in the state since 2017, which is designed to cover a budgetary hole created in part by public spending on the 2016 Olympics, a decrease in the percentage of oil royalties that go to state governments, and the declining price of petroleum.

While most agree that Rio must take action to ameliorate its budgetary crisis, the decision to use CEDAE for this purpose is highly contentious. According to governor Wilson Witzel, contracting out parts of CEDAE may earn Rio up to R$20 billion (US$3.6 billion). But CEDAE is fairly profitable for the government, and its former president Wagner Victer said in a recent interview that if CEDAE remains a public company, it will earn around the equivalent of R$20 billion over the next 17 years.

At a recent online discussion about basic sanitation in favelas hosted by Rio’s Sustainable Favela Network, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro urban studies professor Ana Lucia Britto suggested that Rio’s deficit would be better resolved by addressing misallocation of funds than by privatizing CEDAE. “The local government receives money every month and nobody knows where this money goes. If the local government is responsible for sewerage in the favelas, it should be using the money for this purpose,” she said.

Irenaldo Honório, former president of the residents’ association of the Pica-Pau favela in Rio’s North Zone Cordovil neighborhood, and a committed sanitation activist, pointed out that rampant government corruption has contributed to Rio’s massive debt. “In reality, CEDAE should not be sold to cover the expenses that the previous governor [Sérgio Cabral], who is now in prison, left. His assets have to be paid for, and the debt he created, too.”

Britto further criticized the fact that the virtual public hearings about the privatization process inherently exclude favela voices. “How can you discuss a matter that is going to affect the lives of so many people with hearings that aren’t decentralized and in-person? Favela residents don’t [all] have internet access,” she said.

Some who defend CEDAE’s privatization argue that it will lead to better service provision. They include Edison Carlos, the president of the water and sanitation NGO Trata Brasil Institute. Trata estimates that only 42.9% of the sewage generated in the city of Rio de Janeiro is treated. “In eight years, we haven’t seen any advancement in water treatment,” said Carlos. “We are tired of promises.”

Economist Marco Antonio Rocha of the University of Campinas shared a different view in a recent interview with Nexo: “As healthcare is teaching us, to make a service universal, it has to be public.” He said that the volume of investments needed to universalize sanitation is not very high, but that “the fiscal regime that we’re living under is permitting a universal basic right to go simply unfulfilled.”

“The pandemic shone a light on the sanitation situation in the favelas,” said Ana Lucia Britto. Amid lack of access to full water and sanitation services, favela residents were left to create what solutions they could during the crisis. If privatization of the water utility does not serve them better than the status quo, they may still be decades away from full sanitation access.

This article is part of RioOnWatch’s 2020 reporting partnership with The Rio Times now focused on the impacts of coronavirus on Rio’s favelas.