RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Early last century, Patagonia was the epicenter of a lurid and horrific story that was recorded in ancient chronicles as “The Slaughter of the Turks”, as its main victims were merchants of Arab origin who fell into the clutches of a gang of cannibal thieves who ate their hearts and genitals so as never to be discovered.

The facts were recorded in the Historical Archive of the Province of Río Negro, and have been told in fragments over the years by Argentine media and by journalist Walter Raymond, who dedicated himself to revive the shocking story.

The “Slaughter of the Turks” occurred between 1904 and 1909 and its death toll, according to the records of the officer who investigated it, amounted to some 130 victims, the great majority of them of Syrian-Lebanese origin, who in those years reached Chile and Argentina in large numbers seeking to establish themselves in trade activities.

These itinerant merchants of Arab descent were commonly referred to – and still are – as “Turks,” irrespective of their specific place of origin. But they were also called “mercachifles” because they used to announce themselves in the towns or villages by blowing a kind of whistle or “chifle.”

“They were Lebanese who had just arrived in the country, who left from Neuquén and General Roca, in groups of two and three, accompanied by some laborers and native guides, with horses or mules loaded with clothes, fabrics and other articles,” wrote author

and historian Elías Chucair in a 2009 report.

MISSING “MERCACHIFLES”

The first case of a missing “Turk” was reported in April 1909, in El Cuy, in the heart of the province of Río Negro, in the north part of Patagonia. In those years, the area had only a 150 inhabitants.

The complaint was made by a merchant named Salomon El Dahuk (or Eldahuk, depending on the historical source) because one of his “merchants” named Jose Elias and the laborer who accompanied him (also Arab) Kesen Ezen, had entered Patagonia months before, not to be seen again.

The missing Jose Elias had left General Roca in August 1908, with merchandise from Dahuk, on the agreement that he would return before November. This was a customary tradition of the Syrian-Lebanese, who used to help their newly arrived countrymen to settle with goods on loan so that they could quickly start a profitable activity.

They were last heard from at a place known as “Lanza Niyeo” and a few weeks later their mules and Elijah’s horse were seen wandering the plateau. This had Dahuk worried, as he believed they might have been murdered.

At that time, rumors that “Turks” were being killed in Patagonia had been spreading for years; since 1905, the “mercachifles” who went into the plateau to offer their products in the remote towns and ranches had never returned.

Solomon himself, who had a company called El Dahuk (or Eldahuk) Bros., had a register of 55 traveling merchants, all of Arab origin, who had not returned to pay their merchandise debts.

Given the scale of denunciations, the Río Negro governor Carlos Gallardo appointed Police Chief José Torino, one of the strictest and most rigorous sheriffs in the region, to travel to the site of the disappearances and investigate what had happened. Torino did so and took with him 10 men familiar with the climate and the harshness of the region and set out on the same path as the merchants.

A GANG OF CANNIBALS LED BY A WITCH

The task proved arduous, Torino questioned the inhabitants in search of information but although several claimed to have seen the “Turks” pass by, no one knew more, nor did they shed any light on their whereabouts or destination.

The undertaking seemed to be a total failure until they managed to capture a Mapuche who was responsible for several crimes, but who also knew something about the missing “Turks.” Torino decided to go to “Lagunitas,” a place on the route of the “mercachifles” near Chile, where he found the confession that would guide his search.

The young Mapuche he arrested was called Juan Aburto, and he told him that only three days ago three Syrians had been killed in the toldi (hut) of a certain Ramón Sañico. Not only that, on other occasions they had attacked and killed other Turks who came to the place.

When Torino reached the hut, he did not find the man he was looking for, but he did recover several stolen objects. He was definitely in the right place.

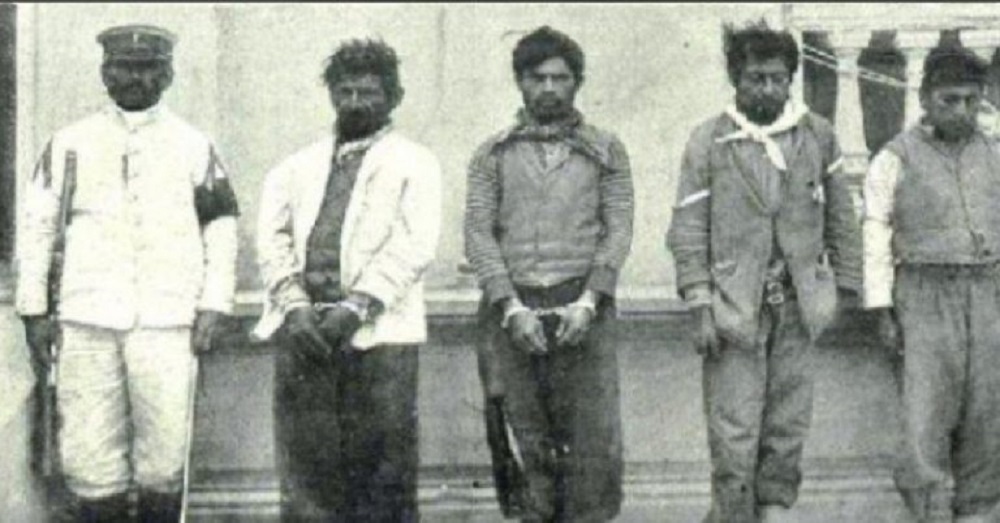

Torino implemented brutal methods to find the gang, capturing and torturing anyone he considered a suspect – questionable but effective methods because in a short time he arrested virtually all members of the gang and collected evidence of their horrific crimes.

Everything was documented in his diaries, especially the references to Antonio Cuece, the gang leader.

He was a special character, because he dressed as a woman and was known by the nickname of “Macagua,” a “machi” – a witch or healer – who had turned his gang of robbers and murderers into cannibals.

The members of the gang were mostly Chilean Mapuche Indians, who raised sheep, horses, hunted ostriches and guanacos. But they were also criminals of the lowest kind who, in the absence of a police force in the region, had found fertile ground for robbery, murder and all kinds of crimes.

Their main victims were the “mercachifles” who came to the region, whom they invited to share roast lamb, wine and other treats, but as soon as their guard dropped they killed them, stole their money, clothes and the merchandise they were carrying.

Under the guidelines of the witch “Macagua,” they extracted their hearts, penises and testicles. With these parts they made amulets for good fortune and success in their criminal enterprises, but they also consumed them in cannibalistic rituals in the belief that it would endow them with virility.

Those parts and others extracted from the corpses of the murdered “Turks” were cooked, roasted and distributed among all of the gang’s members.

“Before eating a piece of the heart of the Turk José Elías, Julián Muñoz said to those present: ‘Before, when I was a capitanejo (subordinate of an Indian chief) and we knew how to fight with the huincas (white men), we knew how to eat Christian hearts; but I have never tasted Turkish and now I am going to know what it tastes like’,” recounts one of the stories recorded in the Río Negro Historical Archive.

Later, what was left of the corpses and belongings were burned and the bones were ground and kept for the “machi” (witch) to make “gualichos” (incantations) with which they avoided being discovered.

According to the testimonies collected and documented by Torino, it was the witch who led them to cannibalism, as she was in charge of extracting the entrails of the murdered men and cutting their private parts, preparing them and giving them to the rest. Many claimed that they began to consume their victims for fear that “Macagua” would bewitch or curse them, and others said that they ate people because “the others had incited them.”

Such was the slaughter, Torino recalls, that one of those captured told him that it had become his habit to eat “steaks of freshly butchered (dead) Turks” for breakfast.

OCCULT POWERS AND TORINO’S MISFORTUNE

In the 4 months of Sheriff Torino’s hunt for cannibals, over 80 people were captured, all accused of being part of the gang that, according to the police chief himself, had murdered and consumed some 130 “Turkish” merchants.

But the alleged gang leader, the witch “Macagua,” was not among those captured. Torino describes her as “an old and dying woman, bedridden with advanced tuberculosis and syphilis, and that is why he did not take her with the rest of the detainees.”

So reads one of Walter Raymond’s reports made in 2017. He further states that weeks after Torino’s departure, it was known that the witch was wandering in the desert. When the latter wanted to arrest her again, sending a police commission for her, he found on a table a paper signed by a powerful patron of the area in which the commissioner was asked to stop chasing the woman “because she was a good person and had done no harm to anyone.”

That was the last thing that was known about the witch “Macagua,” or Antonio Cuece, her real name, who disappeared after that and for years became a legend, a kind of ghost that the inhabitants of Patagonia said they saw wandering around the pampa.

The end of Commissioner Torino is known, as he quickly went from being a hero for dismantling a gang of cannibals to falling into disgrace for the same reason.

The methods Torino employed were not the ‘kindest’ and many of the prisoners he captured ended up dying in prison due to the brutal tortures they were subjected to in order to force them to confess their crimes, and in some cases, to convince them to accept guilt that was not theirs.

All these accusations of abuse of authority and illegal procedures led Torino and his men to a 4-year long trial that culminated in their suspension and imprisonment. None returned to the force, but most of the accused regained their freedom soon after.

Did “Macagua’s” spells work? Some might think so, but according to Raymond’s investigations, everything points to the fact that Torino’s arrests dismantled an illegal trade network that went beyond the detained “capitanejos,” including the “machi” herself, and involved covert politicians and traders in the region who were never known for certain. One of them was Pablo Berbránez, a “huinca” (white man) of Chilean origin who was the real hidden power behind the witch.

They ran a large network, which handled large amounts of money, and Torino had imprisoned the cheap Mapuche labor that kept the network alive at the expense of the lives of the Turkish merchants.

Source: Infobae