RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The challenges indigenous women face begin with their entry into political activity and complicate further if elected as officials amidst tensions with their male peers and the dilemma of exercising their positions under their own convictions or subject to the decisions of their organization.

Cases of pressure on many to resign their posts despite having been elected, forced dismissals and even assassinations such as that of city councilor Juana Quispe in 2012 are part of a contradictory situation in Bolivia, where the presence of women in Parliament must be equal to that of men by law.

THE DIFFICULT EXERCISE OF OFFICE

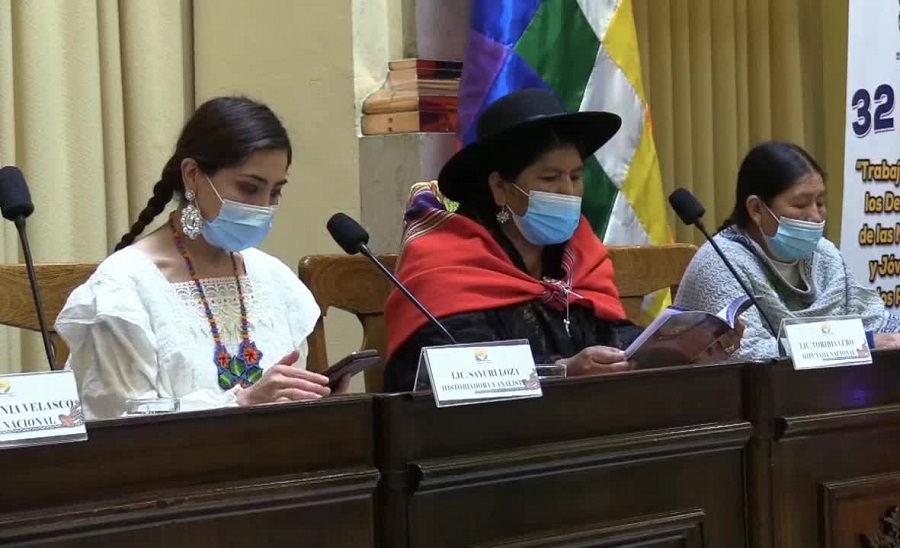

“We see more challenges than progress,” said indigenous legislator Toribia Lero of the opposition Comunidad Ciudadana (CC), because “attacks and violence persist” against women who seek to pursue a career in politics.

In Lero’s opinion, women have “their own” way of doing politics that differentiates them from men based on their “self-determination,” something difficult to achieve in polarized contexts such as the one the country is facing after the 2019 crisis and which has divided positions over “coup d’état” or “electoral fraud” allegations.

The legislator pointed out the difficulty in pursuing a path in politics where she believes there should be a “permanent training” and awareness of the country’s “diversity” to really “produce something” and not merely raise her hand at voting times.

The obstacles she identified stem from a context that continues to be “patriarchal and sexist,” as violence arises both against opposition women because they must “submit” to the majority party and against those in favor of the ruling party, who are asked to “raise their hands collectively” without the option to “decide freely,” she exemplified.

Lero also believes that the 50% quota for women has come to be considered a simple “obligation,” something which she says “is not the case.”

BETWEEN DOMESTIC ROLES AND POLITICS

In much of rural Bolivia, the political role of women must coexist with their household chores, work and animal care, said Teresa Condori, coordinator of the Center for Integral Development of Aimara Women (CDIMA).

Therefore, she considered that indigenous women need “a boost” to exercise public positions in areas where “there is much discrimination” such as the family and political spaces.

The difficulties presented lie mainly in the need for “adequate higher education” and the required “technological skills,” which have become prerequisites for exercising political functions, Condori said.

In fact, a CDIMA publication established that indigenous women “are used by different political parties as symbols of struggle” and that “discrimination” persists in spite of the norms that guarantee “parity and alternation” in the case of elective positions.

“Men disqualify women with the argument that they have no training” and that although there is a real increase of women in politics “this does not mean that they are able to exercise their political rights,” the text points out.

The political participation of women in Bolivia began between 1947 and 1949 when educated women could run for municipal positions, although it was not until 1952 that equal rights were established when universal voting was instituted.

In 1997, a national law established that 30% of lists for parliamentary candidacies should be made up of women, something that was extended to 50% in 2004 by means of parity and alternation criteria.

Currently, 55.6% of the seats in the Senate are held by women and 46.9% in the Chamber of Deputies.